Listeria monocytogenes (page 1)

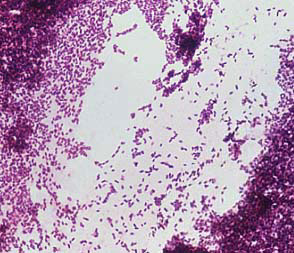

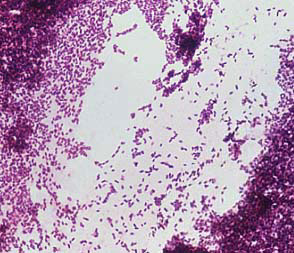

Listeria monocytogenes Gram Stain.

A peculiar property of L. monocytogenes that affects its food-borne transmission is the ability to multiply at low temperatures. The bacteria may therefore grow and accumulate in contaminated food stored in the refrigerator. So it is not surprising that listeriosis is usually associated with ingestion of milk, meat or vegetable products that have been held at refrigeration temperatures for a long period of time.

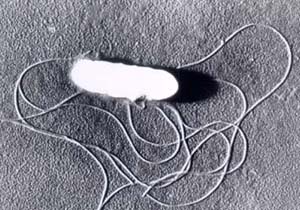

As in the case of Vibrio cholerae, wherein movement, attachment and penetration of the intestinal mucosa are determinants of infection (if not disease), this was thought to be the situation with Listeria, which is also acquired by ingestion and must also find a way to attach to the intestinal mucosa. With cholera, the actively-motile vibrios are thought to use their flagella to swim against the peristaltic movement of the bowel content and to penetrate (by swimming laterally) the mucosal lining of the gut where they adhere. Curiously, although Listeria are actively motile by means of peritrichous flagella at room temperature (20-25°C), the organisms do not synthesize flagella at body temperatures (37°C). Instead, virulence is associated with another type of motility: the ability of the bacteria to move themselves into, within and between host cells by polymerization of host cell actin at one end of the bacterium ("growing actin tails") that can propel the bacteria through cytoplasm. However, one should not totally dismiss the advantage of flagellar motility for existence and spread of the bacteria outside of the immediate host environment.

Listeria monocytogenes Scanning EM showing FlagellaAdherence and invasion

Listeria can attach to and enter mammalian cells. The bacterium is thought to attach to epithelial cells of the GI tract by means of D-galactose residues on the bacterial surface which adhere to D-galactose receptors on the host cells. If this is correct, it is the opposite of the way that most other bacterial pathogens are known to adhere, i.e., the bacterium displays the protein or carbohydrate ligand on its surface and the host displays the amino acid or sugar residue to which the ligand binds. Having said this, macrophages are well known to have "mannose binding receptors" on their surface whose function presumably is to ligand to bacterial surface polysaccharides that terminate in mannose, as a prelude to phagocytic uptake.

Steps in the invasion of cells and intracellular spread by L. monocytogenes. The bacterium apparently invades via the intestinal mucosa. It is thought to attach to intestinal cells by means of D-galactose residues on the bacterial surface which adhere to D-galactose receptors on susceptible intestinal cells The bacterium is taken up (including by non phagocytic cells) by induced phagocytosis, which is thought to be mediated by a membrane associated protein called internalin. Once ingested the bacterium produces listeriolysin (LLO) to escape from the phagosome. The bacterium then multiplies rapidly in the cytoplasm and moves through the cytoplasm to invade adjacent cells by polymerizing actin to form long tails.Other determinants of virulence

L. monocytogenes produces two other hemolysins besides LLO:phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) andphosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC). Unlike LLO, which lyses host cells by forming a pore in the cell membrane, these phospholipases disrupt membrane lipids such as phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylcholine (lecithin).

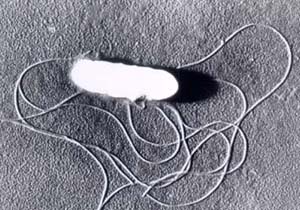

Listeria monocytogenes Scanning EM

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium. It is the agent of listeriosis, a serious infection caused by eating food contaminated with the bacteria. Listeriosis has been recognized as an important public health problem in the United States. The disease affects primarily pregnant women, newborns, and adults with weakened immune systems.

Listeriosis is a serious disease for humans; the overt form of the disease has a mortality greater than 25 percent. The two main clinical manifestations are sepsis and meningitis. Meningitis is often complicated by encephalitis, a pathology that is unusual for bacterial infections.

Microscopically, Listeria species appear as small, Gram-positive rods, which are sometimes arranged in short chains. In direct smears they may be coccoid, so they can be mistaken for streptococci. Longer cells may resemble corynebacteria. Flagella are produced at room temperature but not at 37°C. Hemolytic activity on blood agar has been used as a marker to distinguishListeria monocytogenes among other Listeria species, but it is not an absolutely definitive criterion. Further biochemical characterization may be necessary to distinguish between the different Listeria species.

As Gram-positive, nonsporeforming, catalase-positive rods, the genus Listeriawas classified in the family Corynebacteriaceae through the seventh edition of of Bergey's Manual. 16S rRNA cataloging studies of Stackebrandt et al. (1983) demonstrated that Listeria monocytogenes was a distinct taxon within theLactobacillus-Bacillus branch of the bacterial phylogeny constructed by Woese (1981). In 2001, the Famiiy Listeriaceae was created within the expanding Order Bacillales, which also includes Staphylococcaceae, Bacillaceae and others. Within this phylogeny there are six species of Listeria. The only other genus in the family is Brochothrix.

Listeria monocytogenes Gram Stain.

Natural Habitats of Listeria and Incidence of Disease

Until about 1960, Listeria monocytogenes was thought to be associated almost exclusively with infections in animals, and less frequently in humans. However, in subsequent years, listeriae, including the pathogenic species L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii, began to be isolated from a variety of sources, and they are now recognized to be widely distributed in Nature. In addition to humans, at least 42 species of wild and domestic mammals and 17 avian species, including domestic and game fowl, can harbor listeriae. Listeria monocytogenes is reportedly carried in the intestinal tract of 5-10% of the human population without any apparent symptoms of disease. Listeriae have also been isolated from crustaceans, fish, oysters, ticks, and flies.

The term listeriosis encompasses a wide variety of disease symptoms that are similar in animals and humans. Listeria monocytogenes causes listeriosis in animals and humans; L. ivanovii causes the disease in animals only, mainly sheep. Encephalitis is the most common form of the disease in ruminant animals. In young animals, visceral or septicemic infections often occur. Intra-uterine infection of the fetus via the placenta frequently results in abortion in sheep and cattle.

The true incidence of listeriosis in humans is not known, because in the average healthy adult, infections are usually asymptomatic, or at most produce a mild influenza-like disease. Clinical features range from mild influenza-like symptoms to meningitis and/or meningoencephalitis. Illness is most likely to occur in pregnant women, neonates, the elderly and immunocompromised individuals, but apparently healthy individuals may also be affected. In the serious (overt) form of the disease, meningitis, frequently accompanied by septicemia, is the most commonly encountered disease manifestation. In pregnant women, however, even though the most usual symptom is a mild influenza-like illness without meningitis, infection of the fetus is extremely common and can lead to abortion, stillbirth, or delivery of an acutely ill infant.

In humans, overt listeriosis following infection with L. monocytogenes is usually sporadic, but outbreaks of epidemic proportions have occurred. In 1981, there was an outbreak that involved over 100 people in Canada. Thirty-four of the infections occurred in pregnant women, among whom there were nine stillbirths, 23 infants born infected, and two live healthy births. Among 77 non pregnant adults who developed overt disease, there was nearly 30% mortality. The source of the outbreak was coleslaw produced by a local manufacturer.

One of the most serious and publicized outbreaks of listeriosis occurred in California in 1985 as reported in MMWR, June 21, 1985 / 34(24);357-9.

According to the report, between January 1 and June 14, 1985, 86 cases ofListeria monocytogenes infection were identified in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, California. Fifty-eight of the cases were among mother-infant pairs. Twenty-nine deaths occurred: eight neonatal deaths, 13 stillbirths, and eight non-neonatal deaths. The increased occurrence of listeriosis was first noted at the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center; all cases were in pregnant Hispanics, and all appeared to be community-acquired. A systematic review of laboratory records at hospitals in Los Angeles and Orange County identified additional cases throughout the area.

An analysis of Los Angeles County cases showed that 45 (63%) of the Listeriacases were among mother-newborn pairs. Most (70%) of these women had a prior febrile illness or were febrile on admission to the hospital. Forty-two of the neonatal patients had onset of disease within 24 hours of birth, and all isolates available for testing were serotype 4b. Three of the neonatal patients had late onset disease; only one of the two isolates available for testing was serotype 4b.

Samples of Mexican-style cheeses from three different manufacturers purchased from markets in Los Angeles were cultured at CDC; four packages of one brand of cheese grew L. monocytogenes serotype 4b. The four positive cheese samples were of two varieties, queso fresco and cotija.

In 2002, a multistate outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infections with 46 culture-confirmed cases, seven deaths, and three stillbirths or miscarriages in eight states was linked to eating sliced turkey deli meat. One intact food product and 25 environmental samples from a poultry processing plant yielded L. monocytogenes. Two environmental isolates from floor drains were indistinguishable from that of outbreak patient isolates, suggesting that the plant might be the source of the outbreak.According to the report, between January 1 and June 14, 1985, 86 cases ofListeria monocytogenes infection were identified in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, California. Fifty-eight of the cases were among mother-infant pairs. Twenty-nine deaths occurred: eight neonatal deaths, 13 stillbirths, and eight non-neonatal deaths. The increased occurrence of listeriosis was first noted at the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center; all cases were in pregnant Hispanics, and all appeared to be community-acquired. A systematic review of laboratory records at hospitals in Los Angeles and Orange County identified additional cases throughout the area.

An analysis of Los Angeles County cases showed that 45 (63%) of the Listeriacases were among mother-newborn pairs. Most (70%) of these women had a prior febrile illness or were febrile on admission to the hospital. Forty-two of the neonatal patients had onset of disease within 24 hours of birth, and all isolates available for testing were serotype 4b. Three of the neonatal patients had late onset disease; only one of the two isolates available for testing was serotype 4b.

Samples of Mexican-style cheeses from three different manufacturers purchased from markets in Los Angeles were cultured at CDC; four packages of one brand of cheese grew L. monocytogenes serotype 4b. The four positive cheese samples were of two varieties, queso fresco and cotija.

Pathogenesis

Listeria monocytogenes is presumably ingested with raw, contaminated food. An invasin secreted by the pathogenic bacteria enables the listeriae to penetrate host cells of the epithelial lining. The bacterium is widely distributed so this event may occur frequently. Normally, the immune system eliminates the infection before it spreads. Adults with no history of listeriosis have T lymphocytes primed specifically by Listeria antigens. However, if the immune system is compromised, systemic disease may develop. Listeria monocytogenes multiplies not only extracellularly but also intracellularly, within macrophages after phagocytosis, or within parenchymal cells which are entered by induced phagocytosis.

In mice infected with L. monocytogenes, the bacteria first appear in macrophages and then spread to hepatocytes in the liver. The bacteria stimulate a CMI response that includes the production of TNF, gamma interferon, macrophage activating factors and a cytotoxic T cell response. Possibly, in humans, a failure to control L. monocytogenes by means of CMI allows the bacteria to spread systemically. As well, unlike other bacterial pathogens,Listeria are able to penetrate the endothelial layer of the placenta and thereby infect the fetus.

Virulence Factors

Growth at low temperatures A peculiar property of L. monocytogenes that affects its food-borne transmission is the ability to multiply at low temperatures. The bacteria may therefore grow and accumulate in contaminated food stored in the refrigerator. So it is not surprising that listeriosis is usually associated with ingestion of milk, meat or vegetable products that have been held at refrigeration temperatures for a long period of time.

Growth and viability of Listeria monocytogenes in certain foods at freezing temperatures (-20oC and refrigeration temperatures (4oC) over a 12 week period. Adapted from Baron's (Online) Medical Microbiology: Miscellaneous Pathogenic Bacteria. 2008.

Motility As in the case of Vibrio cholerae, wherein movement, attachment and penetration of the intestinal mucosa are determinants of infection (if not disease), this was thought to be the situation with Listeria, which is also acquired by ingestion and must also find a way to attach to the intestinal mucosa. With cholera, the actively-motile vibrios are thought to use their flagella to swim against the peristaltic movement of the bowel content and to penetrate (by swimming laterally) the mucosal lining of the gut where they adhere. Curiously, although Listeria are actively motile by means of peritrichous flagella at room temperature (20-25°C), the organisms do not synthesize flagella at body temperatures (37°C). Instead, virulence is associated with another type of motility: the ability of the bacteria to move themselves into, within and between host cells by polymerization of host cell actin at one end of the bacterium ("growing actin tails") that can propel the bacteria through cytoplasm. However, one should not totally dismiss the advantage of flagellar motility for existence and spread of the bacteria outside of the immediate host environment.

Listeria monocytogenes Scanning EM showing Flagella

Listeria can attach to and enter mammalian cells. The bacterium is thought to attach to epithelial cells of the GI tract by means of D-galactose residues on the bacterial surface which adhere to D-galactose receptors on the host cells. If this is correct, it is the opposite of the way that most other bacterial pathogens are known to adhere, i.e., the bacterium displays the protein or carbohydrate ligand on its surface and the host displays the amino acid or sugar residue to which the ligand binds. Having said this, macrophages are well known to have "mannose binding receptors" on their surface whose function presumably is to ligand to bacterial surface polysaccharides that terminate in mannose, as a prelude to phagocytic uptake.

The bacteria are then taken up by induced phagocytosis, analogous to the situation in Shigella. An 80 kDa membrane protein called internalin probably mediates invasion. A complement receptor on macrophages has been shown to be the internalin receptor, as well.

After engulfment, the bacterium may escape from the phagosome before phagolysosome fusion occurs mediated by a toxin, which also acts as a hemolysin, listeriolysin O (LLO). This toxin is one of the so-called SH-activated hemolysins, which are produced by a number of other Gram-positive bacteria, such as group A streptococci (streptolysin O), pneumococci (pneumolysin), andClostridium perfringens. The hemolysin gene is located on the chromosome within a cluster of other virulence genes that are all regulated by a common promoter. Survival of the bacterium within the phagolysosome also occurs, aided by the bacterium's ability to produce catalase and superoxide dismutase which neutralize the effects of the phagocytic oxidative burst.

Additional genetic determinants are necessary for further steps in the intracellular life cycle of L. monocytogenes. One particular gene product, Act A (encoded by actA) promotes the polymerization of actin, a component of the host cell cytoskeleton, on the bacterial surface. Within the host cell environment, surrounded by a sheet of actin filaments, the bacteria reside and multiply. The growing actin sheet functions as a propulsive force which drives the bacteria across the intracellular pathways until they finally reach the surface. Then, the host cell is induced to form slim, long protrusions containing living L. monocytogenes. Those cellular projections are engulfed by adjacent cells, including non-professional phagocytes such as parenchymal cells. By such a mechanism, direct cell-to-cell spread of Listeria in an infected tissue may occur without an extracellular stage.

Steps in the invasion of cells and intracellular spread by L. monocytogenes. The bacterium apparently invades via the intestinal mucosa. It is thought to attach to intestinal cells by means of D-galactose residues on the bacterial surface which adhere to D-galactose receptors on susceptible intestinal cells The bacterium is taken up (including by non phagocytic cells) by induced phagocytosis, which is thought to be mediated by a membrane associated protein called internalin. Once ingested the bacterium produces listeriolysin (LLO) to escape from the phagosome. The bacterium then multiplies rapidly in the cytoplasm and moves through the cytoplasm to invade adjacent cells by polymerizing actin to form long tails.

L. monocytogenes produces two other hemolysins besides LLO:phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) andphosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC). Unlike LLO, which lyses host cells by forming a pore in the cell membrane, these phospholipases disrupt membrane lipids such as phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylcholine (lecithin).

The bacterium also produces a Zn++ dependent protease which may act as some sort of exotoxin. Mutations in the encoding gene (mpl) reduce virulence in the mouse model.

Finally, an operon called lmaBA encodes a 20 kDa protein located on the bacterial surface. The protein LMaA induces delayed type hypersensitivity and other CMI responses.

Host Defenses

Because L. monocytogenes multiplies intracellularly, it is largely protected against circulating immune factors (AMI) such as antibodies and complement-mediated lysis. The effective host response is cell-mediated immunity (CMI), involving both lymphokines (especially interferon) produced by CD4+ (TH1) cells and direct lysis of infected cells by CD8+ (Tc) cells. Both of these defense mechanisms are expressed in the microenvironment of the infected foci, which are organized as granulomas, characterized by a central accumulation of macrophages with irregularly shaped nuclei, and by peripheral lymphocytes recognizable by rounded nuclei and a narrow border of intensely staining cytoplasm.

Treatment and Prevention

If diagnosed early enough, antibiotic treatment of pregnant women or immunocompromised individuals can prevent serious consequences of the disease. Antibiotics effective against Listeria species include ampicillin, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, linezolid and azithromycin. However, early diagnosis is the exception rather than the rule, since the first signs of a case or an outbreak are reports of stillbirth or serious infections resembling listeriosis. By then, any cohorts who have become infected from eating the same food are likely recovered from an inapparent or flu-type infection, or they themselves may have developed serious disease. However, processed foods known to be the source of Listeria that may still be in the market place, restaurant or home should obviously not be used, and recalls should be imperative. It must also be constantly recognized that L. monocytogenes is able to grow at low temperatures.

Listeria monocytogenes Scanning EM

Summary

About 2500 cases of listeriosis occur each year in the United States. The initial symptoms are often fever, muscle aches, and sometimes gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea or diarrhea. The illness may be mild and ill persons sometimes describe their illness as flu-like. If infection spreads to the nervous system, symptoms such as headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, or convulsions can occur. Most cases of listeriosis and most deaths occur in adults with weakened immune systems, the elderly, pregnant women, and newborns. However, infections can occur occasionally in otherwise healthy persons. Infections during pregnancy can lead to miscarriages, stillbirths, and infection of newborn infants. Outbreaks of listeriosis have been linked to a variety of foods especially processed meats (such as hot dogs, deli meats, and paté) and dairy products made from unpasteurized milk.

Because pregnant women, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems are at higher risk for listeriosis, CDC recommends the following measures for these persons.

- Do not eat hot dogs and luncheon meats unless they are reheated until steaming hot.

- Avoid cross-contaminating other foods, utensils, and food preparation surfaces with fluid from hot dog packages, and wash hands after handling hot dogs.

- Do not eat soft cheeses such as feta, brie and camembert cheeses, blue-veined cheeses, and Mexican-style cheeses such as "queso blanco fresco." Cheeses that may be eaten include hard cheeses; semi-soft cheeses such as mozzarella; pasteurized processed cheeses such as slices and spreads; cream cheese; and cottage cheese.

- Do not eat refrigerated pâtés or meat spreads. Canned or shelf-stable pâtés and meat spreads may be eaten.

- Do not eat refrigerated smoked seafood, unless it is contained in a cooked dish, such as a casserole. Canned or shelf-stable smoked seafood may be eaten.

- Do not drink raw (unpasteurized) milk or eat foods that contain unpasteurized milk.

No comments:

Post a Comment