X-inactivation (also called lyonization) is a process by which one of the two copies of the X chromosome present in female mammals is inactivated. The inactive X chromosome is silenced by its being packaged in such a way that it has a transcriptionally inactive structure called heterochromatin. As nearly all female mammals have two X chromosomes, X-inactivation prevents them from having twice as many X chromosome gene products as males, who only possess a single copy of the X chromosome (see dosage compensation). The choice of which X chromosome will be inactivated is random in placental mammals such as humans, but once an X chromosome is inactivated it will remain inactive throughout the lifetime of the cell and its descendants in the organism. Unlike the random X-inactivation in placental mammals, inactivation in marsupials applies exclusively to the paternally derived X chromosome.

Mechanism

All mouse cells undergo an early, imprinted inactivation of the paternally-derived X chromosome in two-cell or four-cell stage embryos.[8][9][10] The extraembryonic tissues (which give rise to the placenta and other tissues supporting the embryo) retain this early imprinted inactivation, and thus only the maternal X chromosome is active in these tissues.

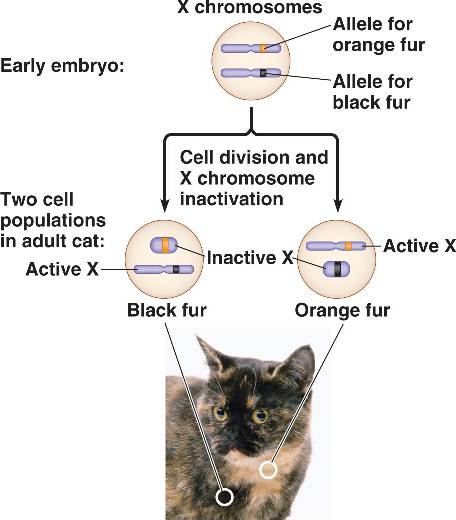

In the early blastocyst, this initial, imprinted X-inactivation is reversed in the cells of the inner cell mass (which give rise to the embryo), and in these cells both X chromosomes become active again. Each of these cells then independently and randomly inactivates one copy of the X chromosome. This inactivation event is irreversible during the lifetime of the cell, so all the descendants of a cell which inactivated a particular X chromosome will also inactivate that same chromosome. This phenomenon, which can be observed in the coloration of tortoiseshell cats when females are heterozygous for the X-linked gene, should not be confused with mosaicism, which is a term that specifically refers to differences in the genotype of various cell populations in the same individual; X-inactivation, which is an epigenetic change that results in a different phenotype, is not a change at the genotypic level. For an individual cell or lineage the inactivation is therefore skewed or 'non-random', and this can give rise to mild symptoms in female 'carriers' of X-linked genetic disorders.[11]

X-inactivation is reversed in the female germline, so that all oocytes contain an active X chromosome.

Selection of one active X chromosome

Normal females possess two X chromosomes, and in any given cell one chromosome will be active (designated as Xa) and one will be inactive (Xi). However, studies of individuals with extra copies of the X chromosome show that in cells with more than two X chromosomes there is still only one Xa, and all the remaining X chromosomes are inactivated. This indicates that the default state of the X chromosome in females is inactivation, but one X chromosome is always selected to remain active.

It is understood that X-chromosome inactivation is a random process, occurring at about the time of gastrulation in the epiblast (cells that will give rise to the embryo). The maternal and paternal X chromosomes have an equal probability of inactivation. This would suggest that women would be expected to suffer from X-linked disorders approximately 50% as often as men[citation needed] (because women have two X chromosomes, while men have only one); however, in actuality, the occurrence of these disorders in females is much lower than that. One explanation for this disparity is that over 25% of genes on the inactivated X chromosome remain expressed, thus providing women with added protection against defective genes coded by the X-chromosome. Some[who?] suggest that this disparity must be proof of preferential (non-random) inactivation. Preferential inactivation of the paternal X-chromosome occurs in both marsupials and in cell lineages that form the membranes surrounding the embryo,[12] but does not occur in the vast majority of our cells

The time period for X-chromosome inactivation explains this disparity. Inactivation occurs in the epiblast during gastrulation, which gives rise to the embryo. Inactivation occurs on a cellular level, resulting in a mosaic expression, in which patches of cells have an inactive maternal X-chromosome, while other patches have an inactive paternal X-chromosome. For example, a female heterozygous for haemophilia (an X-linked disease) would have about half of her liver cells functioning properly, which is typically enough to ensure normal blood clotting Chance could result in significantly more dysfunctional cells; however, such statistical extremes are unlikely. Genetic differences on the chromosome may also render one X-chromosome more likely to undergo inactivation. Also, if one X-chromosome has a mutation hindering its growth or rendering it non viable, cells which randomly inactivated that X will have a selective advantage over cells which randomly inactivated the normal allele. Thus, although inactivation is initially random, cells that inactivate a normal allele (leaving the mutated allele active) will eventually be overgrown and replaced by functionally normal cells in which nearly all have the same X-chromosome activated.

It is hypothesized[by whom?] that there is an autosomally-encoded 'blocking factor' which binds to the X chromosome and prevents its inactivation. The model postulates that there is a limiting blocking factor, so once the available blocking factor molecule binds to one X chromosome the remaining X chromosome(s) are not protected from inactivation. This model is supported by the existence of a single Xa in cells with many X chromosomes and by the existence of two active X chromosomes in cell lines with twice the normal number of autosomes.

Sequences at the X inactivation center (XIC), present on the X chromosome, control the silencing of the X chromosome. The hypothetical blocking factor is predicted to bind to sequences within the XIC.

No comments:

Post a Comment