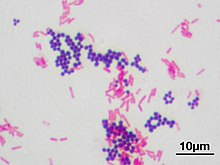

Gram staining, also called Gram's method, is a method of differentiating bacterial species into two large groups (gram-positive and gram-negative). The name comes from its inventor, Hans Christian Gram.

Gram staining differentiates bacteria by the chemical and physical properties of their cell walls by detecting peptidoglycan, which is present in a thick layer in gram-positive bacteria. In a Gram stain test, gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet dye, while a counterstain (commonly safranin or fuchsine) added after the crystal violet gives all gram-negative bacteria a red or pink coloring.

The Gram stain is almost always the first step in the identification of a bacterial organism. While Gram staining is a valuable diagnostic tool in both clinical and research settings, not all bacteria can be definitively classified by this technique. This gives rise to gram-variable and gram-indeterminate groups as well.

Uses

Gram staining is a bacteriological laboratory technique used to differentiate bacterial species into two large groups (gram-positive and gram-negative) based on the physical properties of their cell walls.[5] Gram staining is not used to classify archaea, formerly archaeabacteria, since these microorganisms yield widely varying responses that do not follow their phylogenetic groups.

The Gram stain is not an infallible tool for diagnosis, identification, or phylogeny, and it is of extremely limited use in environmental microbiology. It still competes with molecular techniques even in the medical microbiology lab. Some organisms are gram-variable (that means, they may stain either negative or positive); some organisms are not susceptible to either stain used by the Gram technique. In a modern environmental or molecular microbiology lab, most identification is done using genetic sequences and other molecular techniques, which are far more specific and informative than differential staining.

Gram staining has proven as effective a diagnostic tool as PCR, particularly with regards to gonorrhoea diagnosis in Kuwait. The similarity of the results of both Gram stain and PCR for diagnosis of gonorrhea was 99.4% in Kuwait.

Medical[edit]

See also: Gram-negative bacterial infection and Gram-positive bacterial infection

Gram stains are performed on body fluid or biopsy when infection is suspected. Gram stains yield results much more quickly than culturing, and is especially important when infection would make an important difference in the patient's treatment and prognosis; examples are cerebrospinal fluid for meningitis and synovial fluid for septic arthritis.

Staining mechanism[edit]

Gram-positive bacteria have a thick mesh-like cell wall made of peptidoglycan (50–90% of cell envelope), and as a result are stained purple by crystal violet, whereas gram-negative bacteria have a thinner layer (10% of cell envelope), so do not retain the purple stain and are counter-stained pink by the Safranin. There are four basic steps of the Gram stain:

Applying a primary stain (crystal violet) to a heat-fixed smear of a bacterial culture. Heat fixation kills some bacteria but is mostly used to affix the bacteria to the slide so that they don't rinse out during the staining procedure.

The addition of iodide, which binds to crystal violet and traps it in the cell,

Rapid decolorization with ethanol or acetone, and

Counterstaining with safranin.[9] Carbol fuchsin is sometimes substituted for safranin since it more intensely stains anaerobic bacteria, but it is less commonly used as a counterstain.

Crystal violet (CV) dissociates in aqueous solutions into CV+

and chloride (Cl−

) ions. These ions penetrate through the cell wall and cell membrane of both gram-positive and gram-negative cells. The CV+

ion interacts with negatively charged components of bacterial cells and stains the cells purple.

Iodide (I−

or I−

3) interacts with CV+

and forms large complexes of crystal violet and iodine (CV–I) within the inner and outer layers of the cell. Iodine is often referred to as a mordant, but is a trapping agent that prevents the removal of the CV–I complex and, therefore, color the cell.

When a decolorizer such as alcohol or acetone is added, it interacts with the lipids of the cell membrane. A gram-negative cell loses its outer lipopolysaccharide membrane, and the inner peptidoglycan layer is left exposed. The CV–I complexes are washed from the gram-negative cell along with the outer membrane. In contrast, a gram-positive cell becomes dehydrated from an ethanol treatment. The large CV–I complexes become trapped within the gram-positive cell due to the multilayered nature of its peptidoglycan. The decolorization step is critical and must be timed correctly; the crystal violet stain is removed from both gram-positive and negative cells if the decolorizing agent is left on too long (a matter of seconds).

After decolorization, the gram-positive cell remains purple and the gram-negative cell loses its purple color. Counterstain, which is usually positively charged safranin or basic fuchsine, is applied last to give decolorized gram-negative bacteria a pink or red color.

Some bacteria, after staining with the Gram stain, yield a gram-variable pattern: a mix of pink and purple cells are seen. The genera Actinomyces, Arthobacter, Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, and Propionibacterium have cell walls particularly sensitive to breakage during cell division, resulting in gram-negative staining of these gram-positive cells. In cultures of bacillus, Butyrivibrio, and Clostridium, a decrease in peptidoglycan thickness during growth coincides with an increase in the number of cells that stain gram-negative. In addition, in all bacteria stained using the Gram stain, the age of the culture may influence the results of the stain.

No comments:

Post a Comment